British writer and musician John Phillpott looks at the life and times of Huddie Ledbetter – the legendary Lead Belly – examining his legacy and the wealth of music he bequeathed to future generations of musicians.

IF you were one of the countless post-war ‘baby boomers’ who had acquired a cheap guitar during the mid-1950s, the chances are that once a few primary chords had been mastered, then the next move would have been to learn a Lead Belly song.

Except, of course, you probably wouldn’t have known back then that those alluring tunes with their exotic, compelling themes were by Huddie Ledbetter, bluesman, songster, and ex-convict from Shreveport, Louisiana, who had passed away just a few years previously in 1949.

No. The likelihood was that you’d heard Rock Island Line, Take This Hammer and Pick a Bale of Cotton being sung by a certain Lonnie Donegan, who at the time was popularising a ‘new’ – for the British, that is – music called ‘skiffle’.

Donegan took his first name from the celebrated blues singer and guitarist Lonnie Johnson and was the banjo player with the popular Chris Barber Jazz and Blues Band.

It was also around this time – in 1957 – that Barber, eager to acknowledge the musical contribution of America’s black performers during the era of segregation in their homeland, brought Big Bill Broonzy to British shores.

During the intervals of the band’s sets, Donegan had started to fill the gaps with renditions of Lead Belly songs. Soon, he was appearing on those tiny 1950s monochrome television sets… and the skiffle craze was born.

Skiffle spread like wildfire. All over Britain, young men flocked to music shops, eager to lay their hands on a guitar. The future Beatle John Lennon was one of them, and it’s fair to say that the vast majority of his fellow rock stars-in-waiting would certainly tip their hats to skiffle and the role it had played in their musical development, ultimate fame and considerable fortune.

Nevertheless, it would be some time after the short-lived skiffle mania had died down that the musical legacy of Lead Belly would be fully appreciated.

But while the fascination with American folk music forms grew across Britain as the 1950s moved inexorably into the 1960s, stirring the imagination of the post-war generation, it would not be long before the vast repertoire of Lead Belly would be further explored and – crucially – recorded by this new generation of players that was increasingly taking the music world by storm.

However, this process had already started not long after the singer’s death, when American folk group The Weavers enjoyed a huge hit in 1950 with Goodnight Irene, one of Lead Belly’s last recordings.

It is one of the great, recurring tragedies throughout the history of popular music that fame and its associated financial success came posthumously for Lead Belly. Yet Goodnight Irene would be only the first in a long list of ‘covers’, notwithstanding the fact that as in the Donegan versions, many people who bought the record may not have been aware of its authorship.

In fact, as the years went by, the list would be successively added to by a whole range of artists with varying styles.

With the 1960s in full swing, Lead Belly’s Cotton Song became the Beach Boys’ “Cottonfields“; “House of the Rising Sun” a major hit for British beat group The Animals; and “Black Betty” – a pre-emancipation slave term for the foreman’s whip – proved to be a chart topper for hard rockers Ram Jam in 1977.

I wonder how many people who bought that record at the time knew of the brutal, exploitative origins that led to the inspiration for that song?

As the years went by, there would be a whole host of Lead Belly songs recorded, most notably Ry Cooder’s versions of “The Bourgeois Blues,” “Pigmeat“ and “On a Monday“ that further enhanced the legacy of the now-long-dead musician.

Elsewhere, British rockers Led Zeppelin recorded “Gallows Pole” (“Gallis Pole” by Lead Belly) in 1970, while across the Atlantic the folk and blues trio Koerner, Ray and Glover cut their version of The Titanic on a 1960s album that also showcased the styles and work of several other blues artists.

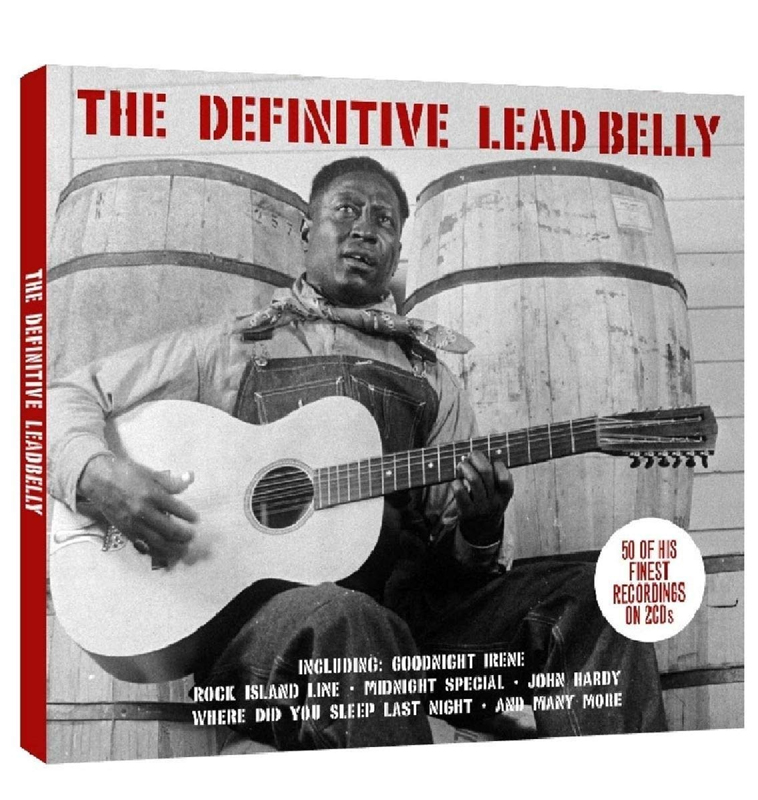

Lead Belly was the archetypical wandering minstrel, playing the work camps, brothels, bars, and joints of the American South. Surviving photographs show a well-built man with an equally big presence and with a big guitar – a Stella 12-string – that echoed the size of its owner.

And it was probably just as well that the singer possessed an imposing presence, for danger and its associated ever-threat of violence was never far away, especially for a black man constantly on the road in the South.

In 1918 Lead Belly killed a relative in a fight. He was sentenced to seven to 35 years in prison (under the alias Walter Boyd) and was incarcerated in Sugar Land Prison in Texas, a notorious prison farm.

Prison governor Pat Neff, a deeply religious man who had campaigned on a strict ‘no pardons’ pledge, often visited the prison to hear Lead Belly perform. The warden, R J Flanagan, would bring Lead Belly to the porch of his house on the prison grounds to entertain guests with his 12-string guitar and songs.

Legend has it that seeing an opportunity, he composed a tune – Governor Pat Neff – and sang it to the governor, the latter being so impressed that he granted Lead Belly an early release.

Lead Belly is also credited with singing another song in Neff’s presence, “Goin’ Back to Mary,” a reference to the singer’s then estranged wife.

Though the official narrative often links his release to the song’s persuasive power, Lead Belly was ultimately pardoned in 1925, just before Neff left office and after serving nearly all his seven-year minimum sentence. He was one of only five convicts Neff pardoned during his entire term.

It was during the next decade that he met the folklorist John A Lomax, who was conducting a series of ‘field’ recordings across the southern states.

Between 1933 and 1947, Lomax, curator of the Archive of American Folk Song of the Library of Congress, together with his son Alan, travelled the Southern states of America doing field recordings in the black prisons of the then-segregated state prison system.

There still exist ‘fly-on-the-wall’ footage of Lead Belly and John A Lomax, but some of these clips do not sit comfortably with modern sensibilities. The singer comes across as being subservient with his white mentor, and although Lomax senior displays a clear regard and affection for Lead Belly, the men’s exchanges do make one wince at times.

The singer’s survival mechanism in a white-dominated world clearly comes into play, his overly respectful approach to Lomax’s overbearing benevolence soon starting to grate on modern ears.

All the same, much credit should go to Lomax, because he subsequently accompanied his ‘discovery’ to New York and introduced him to the predominantly left-wing intelligentsia of Greenwich Village, the city’s bohemian quarter.

Soon, leading lights in what became known as the ‘folk revival’ dipped into the Lead Belly songbook. Tom Rush recorded “Duncan and Brady,” and numerous artists would go on to include “Take This Hammer,” “Black Girl” and “Midnight Special” in their set lists.

Listening to the originals today, it is not always apparent how Lead Belly achieved that distinctive, cathedral-deep sound on his Stella 12-string. But in fact, this can readily be answered because he simply tuned the guitar either three steps down to ‘D’ or five steps down to ‘C’.

Most 12-string players are acutely aware of the risk of damage to their instrument by using medium, let alone heavy gauge strings tuned to European concert pitch, hence lighter gauge strings are often preferred.

But these won’t produce the Leadbelly effect. So, if you – like this 12-string player and Leadbelly devotee – want to sound like the great man, then feel free to opt for the heavier gauges, albeit with the proviso that you tune down… or that guitar neck will certainly be in trouble.

And it’s then – and only then – that you will truly be able to pay homage to a man who bequeathed a fabulous and immortal body of music to the world, one that resolutely rings down the years for listeners and players alike.