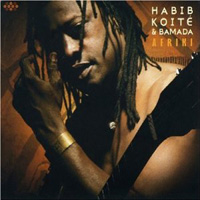

New York (NY), USA – After a six-year absence from the recording studio, Malian guitarist Habib Koité and his band Bamada return this fall with a new album, Afriki. With more than 250,000 albums sold around the globe, an appearance on Late Night with David Letterman, a duet with Bonnie Raitt on her 2001 album Silver Lining and nearly a thousand concerts on some of the world’s most prestigious stages under his belt, Habib Koité is one of Africa’s most beloved and popular musicians. Afriki, which will be released by Cumbancha on September 25th, 2007, features an appealing set of songs that reflect Habib’s unique and innovative approach to the diverse styles of Malian music.

Few African artists have received the sales and media exposure of Habib Koité. Called “Mali’s biggest pop star” by Rolling Stone (in an infamous article in which Bonnie Raitt compared Habib to Jimi Hendrix and Stevie Ray Vaughn). While sales of African music CDs generally struggle to break the 10,000-unit mark, Habib has defied expectations by selling more than 100,000 copies of his last two studio albums, putting him in the upper echelons of world music artist sales. Devoted fans have waited a long time for Habib to return to the studio to record the follow-up to his critically acclaimed 2001 release Baro. As with many craftsmen, Habib is a perfectionist, and spends a great deal of time composing and arranging his material. Unlike others, Habib draws on styles from the different regions of Mali, rather than solely on the music of his particular area. Habib has gained a strong fan base by integrating the rock and folk sounds of the Western world, without watering down his cherished Malian roots. Habib descends from a line of griots, traditional troubadours who provide wit, wisdom and entertainment, and his charisma and magnetism translates across cultures in a way few others have achieved.

Years in the making and recorded on three continents, Afriki finds Habib exploring new musical directions. James Brown veteran Pee Wee Ellis arranged horns on the song “Africa,” which calls upon Africans to take responsibility for their own future and not depend on the outside world. Habib touches on personal subjects, as in “N’ba” (My Mother), an homage to his mother who passed away suddenly while he was on tour. The rousing song “Massaké” (The King) finds humor in the royal status of children who are treated like kings by parents that obey their every whim.

The overarching theme of Afriki, which means “Africa” in the Malian Bambara language, is about the strengths and challenges of the African continent. “People here in Africa are willing to risk death trying to leave for Europe or the USA, but they are not willing to take that risk staying to develop something here in Africa,” says Habib. “Life can be really good or really bad wherever you live. People need to understand that. Even though Mali is poor, we still have good quality of life: You can walk outside and smile and someone will smile back. I have thought about it a lot, and I am not sure if poor countries have a worse quality of life.”

Many of the lyrics on the album follow traditional themes. In the recent tradition of nation-building songs, “Barra,” whose title means “Work,” calls on farmers, fishermen, animal breeders, and tradesmen of Mali to “get organized, get up, and get to work.” Habib is transposing his role of modern-day griot into a facilitator helping fellow Africans survive in the Western-dominated, industrialized world.

Also in the griot tradition, on “Nteri” (“My Friend,” in English), Habib thanks all the people who have shown kindness and generosity to him along the way. He starts with acknowledging ancestors and nearby families, but then generalizes his gratitude:

For all those who have showed me a day of respect

I love you, follow you, and greet you, acknowledge you

Those who unite the masses, stay in front

Those who look after the masses, stay in front

Source of hope and joy, I will always be grateful to you

Because I am satisfied.

“Namania” tells the story of a dark-skinned woman who is always sitting under the shade of a tree by the river. The white of her eyes stands out beautifully. One young man falls in love with her and tells all his city friends, who fall for urban women, that they must come and see this beauty. When the man returns to her tree to find her, she is gone. He calls out, “Where are you? Where are you? I hope you didn’t disappear like the trees across the river.” Habib recalls a farm he visited as a child with his grandfather. All the big trees of the farm were cut down, and the farm was replaced with houses. “In the song, I talk about the things I love so much, and want to keep forever,” Habib explains. “It’s a love song, but it’s also about the things I want to keep.” The sound of the song, which uses the powerful female voice typical of the Songhai, brings to mind the kind of party where this beautiful woman might be.

Afriki emphasizes a tight acoustic sound, showcasing some little-heard traditional instruments such as polyphonic hunter’s horns, alongside bala (wooden xylophone), n’goni (a Malian lute) and Habib’s iconic voice and guitar. “I want to open a small window to the new generations,” explains Habib regarding his use of Malian folk instruments, “to help them hear our old traditions even if it is in new music.”

Buy Afriki.