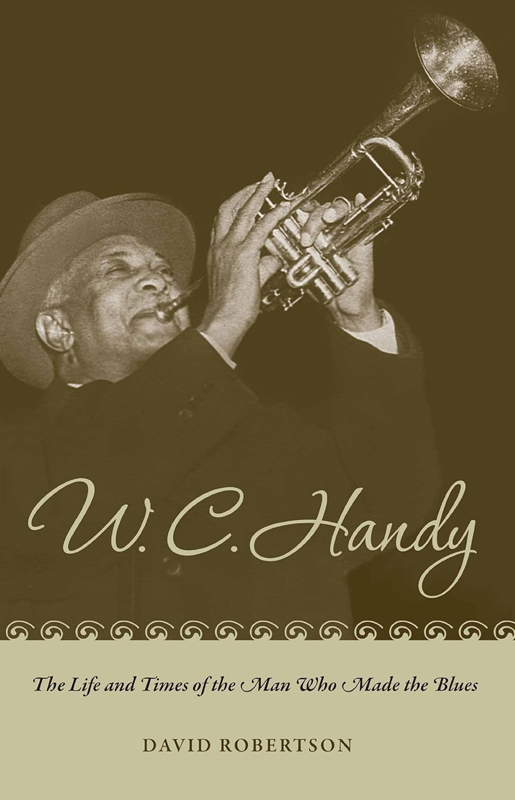

British writer and musician John Phillpott digs deep in the Mississippi mud and unearths the legacy of W. C. Handy, the legendary Father of the Blues… (headline image: Cover of the book W. C. Handy: The Life and Times of the Man Who Made the Blues by David Robertson).

The influence of the blues on American popular music and its wider impact regarding world culture cannot be overstated.

Yet it’s barely a century since its raw, original and untamed fresh-from-the-fields form was harnessed by the composer and band leader W. C. Handy into what would be its familiar 12-bar format.

And slightly less time has elapsed since the publication of the composer’s anthology, compiled from his fast-growing collection of songs bursting forth out of the new, vibrant music.

Handy is, of course, hailed as ‘The Father of the Blues’ and justifiably so. Legend has it that he was waiting for a train at a southern railway station when he saw and heard an old black man playing a guitar, fretting the strings with the blade of a knife.

Handy was captivated by the moaning, plaintive sound, one that would ultimately be copied by countless future musicians across the globe.

For he could probably never have imagined how this technique was destined to become universally recognised and used by both black and white players in the form of the now-commonplace ‘bottleneck’ style.

This is a method by which the guitar’s strings are mainly tuned to an open chord to facilitate both rhythm and melody lines being played simultaneously.

It’s been said that Handy was so entranced by the insistent, anxious urgency of this anonymous musician’s playing that he committed the sound to memory, later notating it at the first available opportunity.

I’ve always thought that this story might have been apocryphal, not because Handy would necessarily have gilded this particular musical lily, rather that he wanted a convenient example to demonstrate his new preoccupation.

Personally, I would have thought that he must surely have encountered any number of itinerant musicians adopting this style on his journeys throughout the Deep South, particularly in his native Mississippi. However, in the absence of any other evidence, this account’s probably as good as any other.

The blues, as we know it, probably started to appear in the early 1900s, among illiterate and disadvantaged blacks. These would be barroom pianists, street corner guitar players, wandering labourers, prostitutes, and outcasts.

While a spiritual lent itself to choral treatment, a blues was very much a one-person affair. Typically, it originated as an expression of the singer’s feeling, completed in a single verse.

It was sung, because singing for this marginalised underclass was as natural a means of expression as speaking. A singer’s idea might never be developed any further, or conversely, eventually develop into a full-blown song.

Perhaps because of its simplicity and suitability for improvisation, one favoured form of the music became increasingly popular – the line would be sung, repeated, and then sung again.

It would not be long before the third repeat would give way to what became known as the ‘resolving line’, in which the previous statements would come to some kind of conclusion or resignation to the situation that had been stated in the first two lines.

W C Handy is credited with establishing the 12-bar format as being the norm, his The St. Louis Blues, recorded in 1914, being one of the first examples. However, there are those who argue that this was not a true blues, as the tune modulates out of the more familiar framework before returning to the melody of the opening verses. Here’s the first verse, which adheres to that 12-bar principle:

I hate to see the evening sun go down

Hate to see the evening sun go down

‘Cause my baby, she done left this town.

Students and scholars have tended to believe that The St. Louis Blues was the first published blues, but this is not correct. For it was in fact a tune titled The Memphis Blues, published some years before in 1909. Its birth was not an easy one… and thereby hangs a tale.

For it was the Memphis, Tennessee idea of advertising, in combination with the city’s febrile politics, that led Handy directly towards his destiny and therefore musical immortality.

In 1909, the fight for the Memphis mayoralty was three-cornered. There were also three leading black bands – Eckford’s, Bynum’s and Handy’s.

These bands were engaged to publicise the executive abilities of the several candidates. Through an agent named Jim Mulcahy, in whose saloon the band had often played, the Handy band was contracted by candidate E H Crump to represent and publicise his interests.

This was an important and wide-reaching commission, involving the organisation of minor bands to cover all possible voting territory, and Handy was inspired to create a tune for the occasion.

Instinctively, he turned to the blues form, which by this time had embedded itself in his thoughts. What he wrote, though, was anything but a lament.

When his band opened with the piece – named, of course, Mr. Crump – on the corner of Main and Madison, it caused dancing in the streets and much great public acclaim.

With such a song, the popular choice was a foregone conclusion. Crump became mayor, and Handy a local celebrity. The mayor was running on a clean-up-the-town platform, so this verse might come as a bit of a surprise…

Mr Crump won’t ‘low no easy riders here

I don’t care what Mr Crump don’t ‘low

I’m gwine to the bar’l house anyhow

Mr Crump can go catch hisself some air.

Whatever the politician in question thought of this last line is not recorded.

The success of the number opened the floodgates to a torrent of follow-up tunes, many of which carried the word ‘blues’ in their titles.

In the summer of 1912, a white man named L. Z. Phillips volunteered to ‘help’ Handy publish a thousand copies of his Mr. Crump and to try them out on the music counter of Bry’s department store, where Phillips worked.

Phillips was employed by Bry’s music store concessionaire Theron C Bennett, a Denver, Colorado publisher. Phillips took the wordless and now retitled The Memphis Blues (Or Mr. Crump) and arranged for it to be printed in Ohio.

On Saturday, September 20, 1909, Handy saw his thousand copies go on sale. But sadly, for Handy the song was not a great success with the public. So, when Bennett offered Handy 50 dollars cash for the copyright itself, royalty-free, Handy agreed.

A few days later, the printer’s records show that Bennett had ordered another 10,000 copies with his own imprint, although this figure has subsequently been disputed. Nevertheless, he wasted no time in capitalising on Handy’s creation.

Bennett then took The Memphis Blues home to Denver, reissued it with success, only with changed lyrics credited to George A Norton, who as Bennett’s staff writer had done a similar job on another famous piece, Ernie Burnett’s My Melancholy Baby.

Bennett made a great deal of money from The Memphis Blues, spent it, and eventually lost ownership. Handy could not – save at a prohibitive price – even obtain permission to include The Memphis Blues in his repertoire.

We can only guess at how he must have felt about being denied a stake in the song that he had created in the first place.

But Handy did not sit back to mourn the loss of his hit, rather sensibly set about producing another one. The St. Louis Blues appeared in 1914, and although it did not sell out, it became the anthem that it remains to this day.

Other great blues numbers followed down the years, and he formed a publishing firm in Memphis, moved to New York in 1919, running the company on Broadway as Handy Bros Music Co Inc.

W. C. Handy was always credited with having an ample sense of humour and philosophical approach to life. And judging by the way things turned out, he certainly needed it.

The author’s thanks are due to Blues: An Anthology edited by W. C. Handy and first published in 1926 (Revised by Jerry Silverman with an introduction by Abbe Niles and illustrations by Miguel Covarrubias in 1972).