Mali’s bluesman Ali Farka Touré has passed the torch onto his son Vieux Farka Touré, whose self-titled first album, Vieux Farka Touré, on World Village Music (US release: February 13; Canada, February 6, 2007) features the final studio recordings of the older Touré before his death in March 2006.

The album, which also features kora-player Toumani Diabaté, draws heavily on the same blues-inflected North African desert traditions that Ali Farka Touré made famous on such albums as the Grammy-winning Ry Cooder collaboration Talking Timbuktu (World Circuit). Vieux’s debut pays musical homage to his father’s roots with familiar trancey guitar-work while incorporating new musical influences from reggae to rock. He will be singing many of these songs on his debut North American tour throughout the Northeast and Canada in early February.

“Here in Africa, he who teaches you in life, you will follow his path,” explains Vieux in his austere yet grounded way. “Our lives here in Mali are like that. Much of what I sing on the album was his wisdom, teachings that he passed down to me. As he neared the end of his life, I knew that the wisdom he imparted on me was important to spread.”

Vieux was not always the obvious successor to Ali’s musical legacy. It wasn’t until Ali had lost much of his movement to bone cancer, when Vieux’s recording was being made, that Ali realized just how musically adept Vieux had become.

Growing up, Vieux played calabash (a unique-sounding dried gourd drum used in Mali) and other percussion, but his father didn’t want Vieux to face the same struggles he had as a musician, and discouraged him from following the same path. The Touré family comes from a noble lineage, in a land where musicians usually come from a musical caste.

Ali went against his own family’s societal role to become a musician and suffered as a result; first toiling to make a living at home in Mali, and then getting cheated by a French producer early in his career. The BBC reported that when he won his first Grammy award, Ali chose not to travel to the United States to collect his prize, saying: “I don’t know what a Grammy means but if someone has something for me, they can come and give it to me here in Niafunké, where I was singing when nobody knew me.”

Ali wanted his son to become a soldier. But Vieux secretly took up the guitar behind closed doors. He enrolled in the Arts Institute in Bamako, the same institution where Habib Koité and many other Malian musicians of note studied. When Ali realized Vieux was not going to give up on playing guitar, he enlisted his good friend Toumani Diabaté as Vieux’s advisor.

When young North American producer Eric Herman of Modiba Productions expressed interest in recording Vieux he had to seek permission from Diabaté, the senior Touré, and other community elders. Once Diabaté and Touré heard Vieux’s initial recordings, they realized they had underestimated the younger Touré’s virtuosity. “Toumani looked shocked,” recalls Herman. “Vieux turned to me and said ‘See, nobody knows I can play music like this.’ I knew… and it didn’t seem to be a secret that he is a really dynamic guitarist. But among the elders who he needed to be respectful of, he was humble and hiding it.”

“Though my father initially resisted my playing music,” explains Vieux, “once he saw that it was truly my ambition and my calling, he was at my side…and he stayed there until the end.”

It’s not surprising that Vieux’s debut album is full of homages to his father, to other elders in his community, and to the people of Mali. That spirit is consistent with the musical tradition and the album strikes a gentle balance between tradition and innovation.

On “Sangaré,” Vieux honors Diadie Sangaré, a longtime friend and confidante of Ali Farka Touré. “My uncle Diadie Sangaré called me in the studio to let me know of a favor he had done for me,” Vieux explains. “Meanwhile, someone next to me bad-mouthed him, and that really angered me… and inspired me to write a song in his honor. I went outside with another guitarist and started working out a line and the song grew from there. We started recording it that same day.”

Another tradition that appears on many of the songs is the teaching of morals. “Africa is not like the West,” says Vieux. “People tell stories, seek their interests behind your back while smiling to your face. I wanted to discuss the hypocrisy in Africa and how people should beware of the results of their actions.”

While the lyrics of “Diallo” honor another “uncle” figure—Barrou Diallo, who played bass with Ali for many years—musically, the track captures the hand off between father and son, with call-and-response guitar solos between the two. “Tabara,” the other track featuring father and son, was written by Toumani Diabaté’s father, another nod of respect. “That was the first track Ali and Vieux recorded together,” remembers Herman, the record’s producer. “That was a completely historic and sublime moment for this musical tradition. Everyone in the studio felt the gravity of it. Ali is almost bleeding through his guitar. He’s one of those musicians that is very linguistic with his instrument. You could feel his pain and suffering.”

The album never strays from Vieux’s essential sound, but gives the listener a diversity of compelling yet accessible timbres. On the two instrumental duets with Toumani Diabaté, the virtuosity of his harp-like kora shows him at the peak of his playing to date. Both tracks were recorded in a single take. After their stunning performance on “Diabaté” (during which neither player could see each other), Toumani says, “Hey Vieux.” “Yeah, father?” responds Vieux from the other recording room. “That was pretty good,” Toumani replies. The two laugh together on this warm dialogue captured on the album.

Songs are peppered with Malian sounds. When he is not demonstrating his strength as a singer and guitarist in his own rite, Vieux expertly plays calabash throughout the album. Mamadou Fofana, from Toumani Diabaté’s band, plays the Guinea flute, an instrument which creates a unique sound when the player literally screams into the flute, and which has rarely been heard in the repertoire of Saharan guitar music. Hassey Sarré, known for his work with Afel Boucoum, plays the njarka, a traditional spike fiddle, on two songs. Tama (talking drum), ngoni (the banjo’s predecessor), and kourignan (scraper) keep the album rooted in tradition as well.

Two songs on the album especially push tradition in new directions. When Toumani Diabaté first listened to “Ana,” he heard the reggae element and encouraged Vieux to develop it further in that direction. The unique combination of Sonrai lyrics and the reggae up beat and horn section create an entry-point for pop music fans. Meanwhile, “Courage” has a distinctly rock sound and gave producer Eric Herman, who wrote the song, the chance to pay his own homage back to the people of Mali. While the song may turn some heads, Vieux is convinced that it is an extension of the tradition from which he comes.

“Music is personal expression,” says Vieux. “Everyone has their own ideas and their way of doing things. No one can replicate what someone else has done. I am working to follow my father’s path, but that path continues into new areas. I am of a new generation, so there are things that inspire me in today’s world that I put in my music, just as he did in his time.”

Vieux Farka Touré is the only recording of father and son playing together. The recording sessions, which took place in the storied Studio Bogolan in Bamako, Mali, had an especially urgent feel to them as Ali was about to make his final trip to Paris for medical attention. Ali Farka Touré’s entourage literally carried him into the studio and placed a guitar in his lap. After forty-five minutes of playing, he was carried back out to his car and headed to the airport. Ali Farka Touré died a few months later back in Bamako. From his hospital bed, he played his son’s new recording for all his visitors, proudly telling them, “That’s my son! That’s me!” His son’s debut album truly represents the embodiment of a legend continued.

Vieux Farka Touré was produced by Modiba Productions, a young production team dedicated to Africa’s empowerment through its music. They are the creators of “ASAP—The Afrobeat Sudan Aid Project,” which has raised over $135,000 dollars for the refugees in Darfur, Sudan. 10% of proceeds from Vieux Farka Toure will be donated to Bee Sago, a UNICEF-affiliated organization, as part of Modiba’s “Fight Malaria” campaign.

With Vieux’s help, they hope to reach their goal of providing every pregnant woman and child in the Touré’s home region of Niafunké with a treated mosquito net—the most effective preventative measure in the fight against malaria, Africa’s leading cause of infant mortality.

“Helping those in Niafunké is something very important to me,” says Vieux. “I want to be able to give back to my village. My father was always vigilant for Niafunké, and I feel it is my duty to continue his work. There are those in Niafunké that don’t have enough to eat, others don’t have medicine, and many children don’t get the chance to grow up because of malaria. If I can do something—if through my music and my album I can help others—that is a gift for us all. It is my privilege to help my people.”

Buy Vieux Farka Toure.

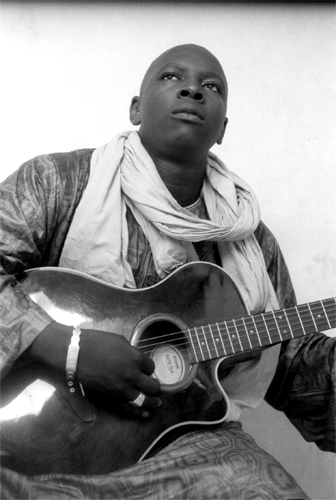

Headline photo: Vieux Farka Toure – Photo Courtesy of Amidou Toure