Writer and musician John Phillpott delves into the darkness of pre-history and unearths a mysterious character known on both sides of the Atlantic by the name of John Barleycorn. But is the age-old folk song in his honour a harmless, whimsical reference to the making of an alcoholic drink, or is there some other, much more sinister meaning?

DURING the middle to late 1960s, artistically adventurous rock musicians on both sides of the Atlantic became increasingly dissatisfied with pop culture’s obsession with the seemingly perpetual subject matter of girl-boy romance.

The Beatles clearly broke the mould with their 1967 album Sergeant Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band but it was not long before darker themes were being explored by the burgeoning rock aristocracy.

The most celebrated of these new Elizabethan Age adventurers were, of course, Britain’s Rolling Stones. Although they hadn’t entirely dumped their rhythm and blues roots, Mick Jagger and Keith Richards were now starting to look to the occult for inspiration.

Sympathy for The Devil – a dark tale of demonic possession and its relevance to past and present world leaders’ influence on global events – was perhaps the best-known and most celebrated, notorious track of that era.

However, an album released in 1970 arguably delved much deeper into the human folk memory, featuring a track that probed an even darker and distant pre-history, of a time in the British Isles when there was no written record of human existence… the Age of the Celts.

John Barleycorn Must Die was the fourth studio album by English rock band Traffic, released in that year as Island ILPS 9116 in the UK, United Artists UAS 5504 in the United States, and as Polydor 2334 013 in Canada.

It marked the band’s comeback after a brief disbandment and peaked at number 5 on the Billboard Top LPs chart, making it the band’s highest-charting album in America. However, this was not just another album track, for the ancestry of this song went back several millennia.

So, WHO was John Barleycorn? Was he man or myth? And do those spectacularly obscure and weird lyrics hint at some kind of ritual killing, of a time when the gods had to be placated to ensure that nothing but good fortune befell the community?

From all the available evidence, we first come across John Barleycorn as the titular character of a popular English and Scottish folk song, found in a number of versions going back, at least, to the 16th century.

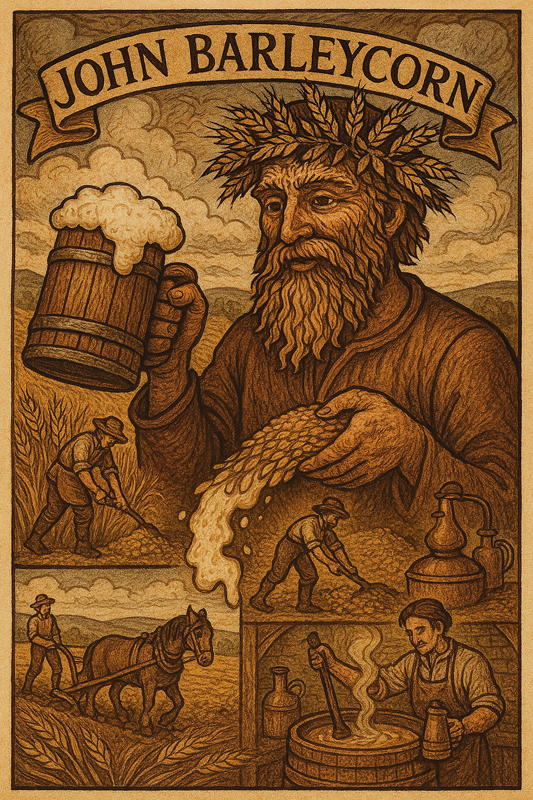

John Barleycorn is given as the personification of ‘the nut-brown ale’ (or the uisce beatha) and all the process the grain goes through in order to provide the drink. The song also celebrates the many occupations and trades people who work towards the creation of the intoxicating liquid.

The first mention of John Barleycorn as a character was in a 1624 London broadside introduced as A Pleasant New Ballad to sing Evening and morn, Of the Bloody murder of Sir John Barley-corn. The following two verses are from this 1624 version:

Yestreen, I heard a pleasant greeting

A pleasant toy and full of joy, two noblemen were meeting

And as they walked for to sport, upon a summer’s day,

Then with another nobleman, they went to make affray

Whose names was Sir John Barleycorn, he dwelt down in a dale,

Who had a kinsman lived nearby, they called him Thomas Good Ale,

Another named Richard Beer, was ready at that time,

Another worthy knight was there, called Sir William White Wine.

Nevertheless, this harmless portrayal may merely skim the theoretical surface, the processes that create an alcoholic drink perhaps being a metaphor for the deliberate murder and torture of the character in the song.

But this begs the question – do we take the words to the song literally, or see behind what may be a lyrical smokescreen to view a brutal truth?

For we learn that John Barleycorn is buried, chopped down, beaten, bound and ground up. In fact, the song generally begins with an oath being taken to kill him and his death is celebrated with each stanza.

The true antiquity of the song cannot be proved. And yet it seems to be more than an amusing metaphor for acknowledging the origin of ale or whiskey.

For the fact remains that it is hard not to find connections between John Barleycorn and the ancient culture heroes of the Bronze Age who are cut down only to rise up again, reborn with the annual new growth of the crops.

Human sacrifice was widely practised by the Celts to ensure precisely that – the continuation of the earth’s bounty and the necessary homage to the sun, which made fruitfulness possible.

It was only through the blood of the chosen victim sinking into the soil, thereby replenishing it, that future fertility could be guaranteed.

There is evidence of this practice. From time to time, sacrificial victims are unearthed in Britain and across Europe, in some cases the bodies being so well preserved that it is possible to detect their last meal. Were these the John Barleycorn’s of Antiquity?

And it’s entirely possible that ancient societies elsewhere also practised similar deadly ceremonies. Many of the so-called ‘mystery cults’ of the Middle East with their familiar heroes, Damuzi, Attis and Adonis, may share something with Britain’s more homely John Barleycorn.

That they were connected with herb, vegetable and grain crops can be readily demonstrated. Osiris, one of the most popular of the culture heroes of ancient Egypt, was said to have brought the arts of civilization to the Ancient World, including knowledge of cultivation.

Osiris was threatened by his brother Set, Lord of the storm and desert places, and aided by his sister and wife, Isis, who restored him to life after he was cut down by Set, by gathering up the pieces of his scattered body.

Superficially, in English folklore, John Barleycorn is a just a character who represents the crop of barley harvested each autumn, and the song that celebrates his demise survived into the 20th century in the oral folk tradition, primarily in England.

In most traditional versions, including the 16th century Scottish version entitled Alan-a-Maut, the plant’s ill-treatment by humans and its re-emergence as beer, leading to acts of revenge, are key themes.

In recorded history, we first hear of John Barleycorn in 1620. Like so much music from the British Isles, it’s not long before he crops up in colonial America, transported by human migration to the New World.

British sources often refer to the character as Sir John Barleycorn, as in a 17th-century pamphlet The Arraigning and Indicting of Sir John Barleycorn, Knight, and in a ballad found in The English Dancing Master (1651).

Versions of the song John Barleycorn date back to the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, but there is evidence that it was sung for many years before that. Sir James Frazer cites John Barleycorn as proof that there was once a Pagan cult in England that worshipped a god of vegetation, who was sacrificed to bring fertility to the fields.

In early Anglo-Saxon Paganism, there was a figure called Beowa, associated with the threshing of the grain, and agriculture in general. Some scholars believe this individual was the source of the Beowulf epic.

There are several different more modern versions, but the most well-known one is the version by the 18th century Scottish poet Robert Burns, in which John Barleycorn is portrayed as an almost Christ-like figure, suffering greatly before finally dying so that others may live.

A version of the song is included in the Bannatyne Manuscript of 1568, and English broadside versions from the 17th century are common. Robert Burns published his own version in 1782.

Nearer our own times, many field recordings of the song were made of traditional singers performing the song, mostly in England. In 1908, Percy Grainger used phonograph technology to record a Lincolnshire man named William Short singing the song. The recording can be heard on the British Library Sound Archive website.

And James Madison Carpenter recorded a fragment sung by a Harry Wiltshire of Wheald, Oxfordshire in the 1930s, which is available on the Ralph Vaughan Williams Memorial Library website as well as another version probably performed by a Charles Phelps of Avening, Gloucestershire.

The Shropshire singer Fred Jordan was also recorded singing a traditional version in the 1960s. And a version recorded in Doolin, Co Clare, Ireland from a Michael Flanagan during the 1970s, can be obtained courtesy of the County Clare Library.

Elsewhere, the Scottish singer Duncan Williamson cut a traditional version and Helen Hartness Flanders recorded a version sung by a man named Thomas Armstrong of Mooers Forks, New York, USA in 1935.

Not to be outdone, in the world of western classical music, the composer and folklorist Vaughan Williams used a version of the song in his English Folk Song Suite in 1923.

However, no amount of jollity and the celebration of eating and drinking can disguise what might indeed be the real origins of the ballad.

In The Golden Bough, Sir James Frazer cites John Barleycorn as proof that there was once a Pagan cult in England that worshipped a god of vegetation, who was sacrificed in order to bring fertility to the fields.

This ties into the related story of the Wicker Man, who is not only burned in effigy, but also in reality, too. The 1973 cult film The Wicker Man, in which a hapless policeman is sacrificially burned alive along with a collection of animals, was a more recent manifestation of this enduring legend.

Therefore, considering the many pagan themes in the story, it’s likely that the origins lie in Pre-Christian times. Specifically, there may even be a link between the name John Barleycorn and the mythical figure Beowa, whose name in Anglo-Saxon Paganism means ‘barley’. Yet it is still impossible not to draw other conclusions, as hinted at in these lines from the song:

They laid him out upon the floor,

To work him further woe;

And still, as signs of life appear’d,

They toss’d him to and fro.

And who exactly were the characters in the opening verse, who bring about John Barleycorn’s downfall, having earlier vowed that his fate had been sealed?

There were three men come out of the west,

their fortunes for to try,

And these three men made a solemn vow,

John Barleycorn would die

It’s interesting that we start with three men coming out of the West. Many of us are familiar with the religious importance of the number three – there may indeed be great symbolism attached to this number.

The ‘three men’ – perhaps a reference to the Biblical Three Kings or ‘wise men’? And then there’s John Barleycorn himself, sentenced to endure a prolonged, agonising death – is he really Jesus Christ the Messiah, and could his nemesis be an amalgam of Pontius Pilate, Judas and the Pharisees?

Furthermore, the triad and triple spiral are famous symbols in Celtic paganism. It’s also possible that these men are coming from the West, because in Celtic myths, coming from ‘The West’ meant visiting from the Otherworld.

So, there you have it. John Barleycorn, that familiar centuries-old figure in folksong, must – and has – certainly died many times down the ages.

Yet symbolically and paradoxically, the ritualised slaughter of John Barleycorn also guarantees his immortality… just as the success of the harvest had to be assured for perpetuity in a time when superstition and fear, rather than reason, stalked the wilderness lands of pre-history.