This month – June – sees the 20th anniversary of the death of John Lee Hooker, one of the most influential blues artists of all time. Writer and musician John Phillpott recalls how, as a 16-year-old rookie newspaper reporter, he met the great man in his local dance hall…

The corridor was hot. The air smelled of stale cigarette smoke and sweat… and to increase the suffocating and fetid feel, a bulb in the ceiling was flickering on and off, like a strobe light going through its death throes.

A door opened. It was the drummer from London rock group The Machine. He was expecting me, as we’d talked on the phone earlier.

Raising an eyebrow by way of recognition, he said: “Are you the chap from the Rugby Advertiser?” I nodded, while at the same time fumbling to find my press card.

“You can come in. John Lee Hooker’s right here.”

That’s right… sitting at a table was John Lee Hooker, famed American bluesman, playing a gig in my town tonight. And I’ve managed to convince him that I’m capable of doing the man justice with an interview.

As an apprentice blues fan, I was already familiar with Hooker’s Crawling King Snake, and particularly liked his version of One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer, songwriter Rudy Toombs’ magnificent homage to the joys and perils of alcohol, which had first been recorded by Amos Milburn back in 1953.

But let’s wind back my own tape for just a moment. I’d started work on the Rugby Advertiser the previous summer, aged just 16. Now it was March, 1966, and with a mere eight months’ experience under my belt, had nevertheless already covered golden weddings, flower shows and a particularly nasty car crash. It was my first view of a mangled, very dead body. It would not be the last.

When not engaged in such diverse pursuits, on Saturday nights I had started wandering down to the local dance hall in order to meet visiting rock stars of the day.

I’d already met John Mayall’s Bluesbreakers, a few pop acts, and now it was to be John Lee Hooker. I couldn’t believe my luck.

Here’s another brief pause, this time for a bit of English Midlands history. Thanks to its geographical position at the centre of Britain, and the fast-emerging hub of the new motorway network, the town was hosting top acts most weeks at its premier venue, the Benn Memorial Hall.

By the standards of the time, it was quite a large building, boasting a generously wide stage, dressing rooms, an auditorium, and a bar situated just to the left, accessible only after you had walked past the beady-eyed security men.

I say men, but some of them would have been barely out of their teens, local hard men with broken noses that were testament to their specialised calling, and with bulging biceps visibly stretching the fabric of cheap off-the-peg suits.

By 1966, rhythm and blues was very big in Rugby. Like most towns and cities back then, many young people had become fascinated and mesmerised by African-American music, blues, Tamla Motown and a gospel-inspired sound that would later become known as Soul.

So-called ‘trad’ jazz had merely scratched the surface during the 1950s, originally brought to Britain by US servicemen the decade before.

And earlier still, this relentless American invasion had delivered ragtime to a receptive population, who were soon to be completely seduced by alien influences with the advent of the 1930s dance bands and their chocolate-smooth massed saxophone harmonies.

What these different musical forms did was to create a mythology of a far-off land where dreams could – and often did – come true. It’s little wonder Britain was soon to sleepwalk into the most destructive war in the history of the world. We’d taken our eye off Europe and become hypnotised by America. Well, that’s not the only reason, of course.

But there was one big difference between Scott Joplin’s fingers dancing over the ivories, crooners with voices creamier than caramel, and the new music coming across the Atlantic.

For this latest incursion took the form of a gutsy, no nonsense music that, when it came to raw emotion, most certainly didn’t take prisoners.

Once, it had been the moon in June. Now it was sex. For drinks on the terrace with your intended, it was enjoying an old fruit jar full of bootleg hooch with your easy rider.

And for undying fidelity, read two-timing lovers and riding the blinds to seek a better future… got the key to the highway, gonna leave here running because walking is most too slow.

We’re back in real time. John Lee Hooker opens with Dimples, a lurching 12-bar shuffle that would soon become the universal currency in dance halls, record stores and record players in a thousand and one bedrooms and front rooms.

By the 1960s, much of the indigenous folk music of the British Isles had basically become museum exhibits, preserved not in glass jars filled with formaldehyde, but in folk clubs up and down the land.

No longer were age-old songs such as Barbara Allen and The Soldier and the Lady sung by rustic sons of the soil who had left hoe and pitchfork outside propped up against the cider house wall.

The decline of English folk music, essentially a rural art, had virtually withered and died in the new, expanding towns that were now rapidly swallowing the countryside as the Industrial Revolution gathered pace.

And while it was perfectly true that the migration to urban areas spawned their own body of industrial songs, these were destined never to completely take root among the general population whose entire lives were now consumed from dawn till dusk by work.

Once, people had worked in harmony with the passing seasons. Now they laboured to the dictates of the factory hooter and the overseer’s ever-watchful gaze.

For a labour-exhausted workforce, there was now little time for recreation in England’s formerly green and pleasant land, let alone folk music.

It was only on the geographical British Isles’ Celtic fringes – Scotland, Wales and Ireland – that anything remotely like a folk tradition remained. Here in England, the folk memory hung on by its fingertips, the preserve of collectors such as Cecil Sharpe, and the now fast-growing educated middle class bourgeoisie.

There would eventually be a vacuum to be filled, one that by the early 1960s had become a void. But it was soon to be filled

And John Lee Hooker, perhaps not a little amazed at his success and popularity among British people young enough to be his sons and daughters, embodied the sea change that had been brought about.

Hooker’s birth date has variously been given as 1912 or 1923 in Tutwiler or Clarksdale, Mississippi, but – as confirmed by the man himself when I spoke to him – it was indeed the latter town and the date had been 1917…

We’re back in real time again. John Lee Hooker closes Dimples and almost immediately launches into Boom, Boom. The crowd goes wild, there are shouts of recognition. Yes, yes, we know this one.

Even as early as 1966, Boom, Boom had become a set list staple for British groups such as The Animals, The Yardbirds and countless other bands that would enjoy regional fame, but eventually disappear from sight as fickle youth moved on to the next musical fashion.

But for Hooker, this would be the springtime of his fame, not only in Britain, but across the world.

Boom, Boom concludes with a typical ‘deep chord’ ending in the key of ‘E’. Throughout his career, John Lee Hooker basically used two keys, ‘E’ and open ‘G’ tuning. Future musicologists may well argue about this, but all the evidence points to these being the keys that best lent themselves to Hooker’s enigmatic and minimalist technique.

You can hear the latter tuning to best effect in his Boogie Chillen, a choked, repetitive bass riff followed by a stabbing, flattened seventh chord caught on the upstroke.

And if you’re not moved to move to this, then I doubt whether you’re in possession of a functioning pulse, my friends.

We’re back on stage. Now it’s I’m in the Mood followed by I Cover the Waterfront, two tracks from his recently released The Real Folk Blues album. Somehow, The Machine manages to cope with Hooker’s famously inventive and erratic sense of timing.

But what of the interview itself? There is just one question I put to him that I can remember from that long-gone March night back in 1966. I asked him to define the blues.

His response? The blues ain’t nothing but a good man feeling bad…

And that marvellously succinct definition has remained with me down all these years of reading, writing and messing about with the blues on both guitar and harmonica.

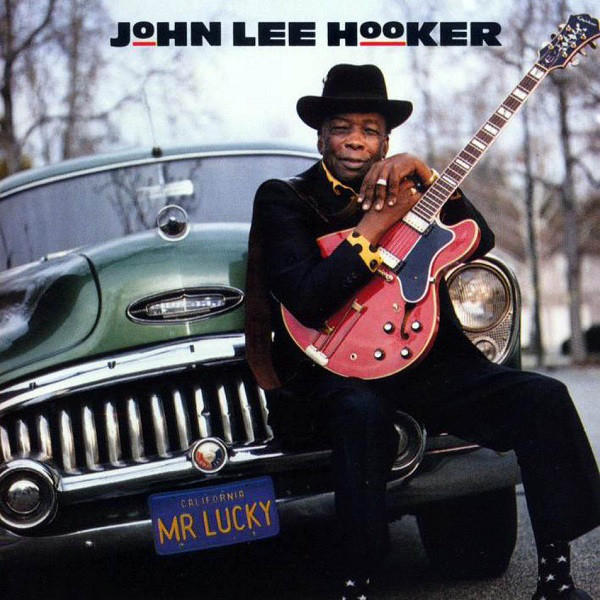

John Lee Hooker died in his sleep on June 21, 2001. In later years, he had collaborated with several of the world’s top rock stars who had been so influenced by his playing, recording albums such as The Healer, Mr Lucky, Chill Out and Don’t Look Back.

The man from the Mississippi Delta was arguably the last of his generation of country bluesmen, leaving an immortal legacy. And while there would be other artists who visited Britain’s shores during the blues boom 1960s, few would rival Hooker in terms of lasting influence.

For the man invariably pictured holding what seemed to be an oversized Epiphone or Gibson guitar might have been short in stature, yet was indeed a giant by reputation.

And without doubt, he must surely have touched the lives of thousands of guitarists down the years – including this one here – and for that I will always be in his debt.

Sleep tight in Blues Heaven, John Lee!