The teenage John Phillpott went down to the local cinema rather than the crossroads… and there he encountered the man who was arguably the founding father of what would become known as World Music.

The late piano player Otis Spann once told writer and musicologist Paul Oliver that the blues “began in the lowlands”.

He was, of course, referring to the Mississippi Delta, and spoke these words during a taped interview that can he heard on the iconic album Conversation with the Blues, a groundbreaking chunk of vinyl from the 1960s that first generation English bluesmen such as myself played until the sound was not so much catfish and grits, rather bacon and eggs.

If that poor old, overworked stylus ever screamed for mercy, then I just didn’t hear it. I was too obsessed with listening to Spann, J B Lenoir, John Lee Hooker and the other now departed trailblazers of a music that we were soon to love so much.

All right. That was where the music evolved across the Pond. But what about here in good old Blighty, and how – arguably, of course – did the British Blues sound get a foothold?

For me, and undoubtedly countless other youngsters, it almost certainly started after seeing the first incarnation of the Rolling Stones. In my case, this was in February, 1964, and the setting was the Granada cinema, Rugby, Warwickshire, England.

Imagine a time when The Stones played cinemas…

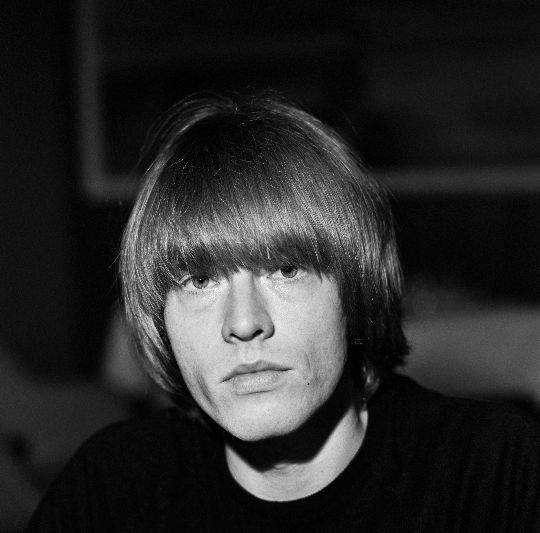

The star of the show back then was undeniably group founder Brian Jones. Forget for a moment his catastrophic descent into decadence and musical impotence as the 1960s drew to a close, here he was at the threshold of his powers.

Yet for nearly five decades, he has been depicted as the androgynous, drug-addled rock and roll hedonist, the hell-raiser who flew too fast and ran out of runway.

There is no doubt that his leering, lantern-jawed face might have for long been stuck fast in the permafrost of eternity. But the dark-shadowed eyes, staring beneath that trademark blond fringe of hair, actually conceal a deeper, more fundamental truth.

And it’s one that magnificently transcends his miserable death – almost certainly murder – in the swimming pool of his home at Cotchford Farm, Sussex, on the night of July 2-3, 1969.

It’s this. Brian Jones was, in my view, the founding father of what we call World Music. Without him, I would submit, the whole process might never have started. The debt we owe him is beyond calculation.

But first, let us return to the Granada cinema, Rugby, on that bitterly cold February night back in 1964…

It’s intoxicating, mesmeric. The slide guitar on I Wanna Be Your Man. The train-time harmonica chug-a-chug on Not Fade Away… and even more stabbing harp riffs on Bo Diddley’s Cops and Robbers.

To be sure, the band’s version might well have been inferior to that of Elias McDaniel’s. But it didn’t matter. For here we had, for the first time, those twin ingredients that make for the beating heart of the blues – the eerie sound of bottleneck guitar and almost unearthly wail of the mouth harp. Yes, yes… I don’t just want to watch and listen, I need to grab a slice of the action myself. I want to do it, too. Tomorrow. No, now!

So. That Saturday morning following the show, I went in to Berwick’s music shop in Rugby’s Sheep Street, and bought an Echo Super Vamper harmonica for the princely sum of 10 shillings (50p).

I can see it now. There it was, snug in that little blue box, silvery bright with a shiny row of light brown wooden reeds, a perfect set of teeth for a perfect little instrument.

I had begun the love affair of a lifetime for which the heat and the passion would neither wane nor falter.

My first attempts were not exactly brimming with promise. Before long, I had mastered Home on the Range, but this was hardly the symphony of the Louisiana swamplands.

You see, in a world of no instruction books, no YouTube, no online lessons, let alone mates who could explain that you had to suck and tease the notes with your tongue, it was hard going to say the least.

And yet… I prevailed. After all these years, practice may not have made perfect, but I’d like to think I can blow with the best of them.

In fact, back in October, 2015, I was interviewed and filmed by a production company working for what would be a BBC4 series titled The People’s History of Pop.

This was broadcast in the spring of the next year and it featured me not only reminiscing about the Stones gig all those years before, but also playing ‘cross-harp’ along with an archive film of the boys themselves performing the Buddy Holly classic that had once so memorably fired my imagination.

Fifty-seven years after the band rocked my home town, I have a small suitcase packed with harmonicas. There are diatonics, chromatics, many still play, others have blown out reeds.

It doesn’t matter, for all of them bring back memories of gigs, jamming with friends, or lonesome blowing on some hillside, beach or old disused railroad track.

Yes, really, I’ve really tried to live the dream, once accompanying a freight train as it crossed a bridge over the Potomac river in West Virginia. Who cares if some people think you’re mad?

But let us rejoin Brian Jones for a moment just hours after he has left that cinema’s stage in my English Midlands home town. I buy the harmonica, and a while later, somehow manage to pick up a battered guitar for 30 shillings (£1.50).

Long before I have learnt to fret chords, I have somehow discovered open ‘G’ tuning and managed to work out Muddy Waters’ Can’t Be Satisfied, as played by Jones on the Stones’ second album. Pure bliss.

There is little doubt that the early Rolling Stones sound was driven by Brian Jones. Even during the height of the rhythm and blues covers period, he was adding all manner of – what were then exotic – touches of musical colour to Stones tracks.

There was the dulcimer on Lady Jane, the marimba riffs on Under My Thumb… even a recorder on Ruby Tuesday.

Make no mistake. The seeds of World Music were being sown. Slowly but surely, a wider acceptance of what had hitherto been folk – rather than pop instruments – was gathering pace

Brian Jones’ eclectic choice of instrumentation was previously unheard of in the world of the three-minute single. It’s no wonder and entirely logical that by 1967, Jones was recording and absorbing the music of the Joujouka [also spelled Jajouka] people of Morocco.

He may have lost the love of Anita Pallenberg to fellow Stone Keith Richards on that holiday, but he had most certainly won through to his musical destiny.

And what other future musical journeys would he have taken had he lived and not died in that swimming pool in the summer of 1969? The question remains, yet the answer lies tantalisingly out of reach.

For me, the blues has been a lifelong journey. I never tire of it, still gain comfort from it, and I often reflect that nothing would have been the same had I not seen the Stones all that time ago in that long-gone cinema with its sticky carpets and fug of stale tobacco smoke.

But despite the passage of the years, I still pay musical homage to the man who – in my view, at least – would prove to be the founding father of what would become known as World Music.

A couple of years ago, I visited Brian Jones’ grave in Cheltenham and quietly meditated on the unsung hero who not only enriched my life, but also the lives of countless other youngsters of my generation who had followed a certain Pied Piper along the road to musical happiness.

Footnote: John Phillpott is a journalist and author. His latest book, Go and Make the Tea, Boy! is an account of his life working as a trainee reporter on a weekly newspaper during the 1960s.

[headline photo: Brian Jones of The Rolling Stones during the band’s visit to Finland – Photo by Olavi Kaskisuo / Lehtikuva]

Really loved reading this! As much as I respect and have read about about Brian, somehow I never made the (seems so obvious now) link to world music. Brilliant!

His death was covered up by Scotland Yard commander Wallace Virgo.

Brian Jones was a very under appreciated musician. He and the Stones brought American blues more to the public eye – even in America, and, yes, he was one of the pioneers of World Music. He was also an amazing colorist with all the different instruments he played.