Writer and musician John Phillpott explores the drinking dens of Victorian England and uncovers the musical underbelly of that so-called prudish age…

A POPULAR show on British television during the 1960s and 70s was Old Time Music Hall, a weekly visit to an era before the First World War when the working masses sought solace in the theater as a welcome break from the seemingly endless cycle of farm and factory.

Presented by master of ceremonies Leonard Sachs, each episode featured actors portraying the stars of the late Victorian period, performers such as Vesta Tilley, Marie Lloyd, Annie Adams, Fred Albert and Charles Austin.

Songs such as Down at the Old Bull and Bush, Two Lovely Black Eyes and Don’t Dilly Dally on the Way were revived and sung with great enthusiasm by present-day audiences suitably dressed in the clothes of the period.

There were gentlemen in top hats and tails, British soldiers wearing red tunics, and women resplendent with all the fashionable glories of the late Victorian and Edwardian ages.

Leonard Sachs was a renowned master of alliteration, and his announcements were always peppered with absurdly extravagant turns of phrase. But above all, apart from the mildest innuendo, all the acts maintained a fairly strict code of decency, avoiding even the merest suggestion of impropriety.

However, behind all those cloaks of respectability lay the darker clothes of vulgar truth. And perhaps the word ‘vulgar’ would be putting it too mildly.

For the origins of the British Music Hall tradition lay in songs that were too filthy for all but the most unshockable inhabitants of the drinking dens and taverns of England, places of ill repute with reputations far removed from the widely held notion of Victorian snobbery and prudishness.

Historically, sexual innuendo had always been a feature of many British folk songs, yet they were often pillaged, then cleaned up for polite, church-going society. For example, a song such as The Blacksmith, a tune laced with sexual imagery, had found new life in the Protestant hymn To Be a Pilgrim.

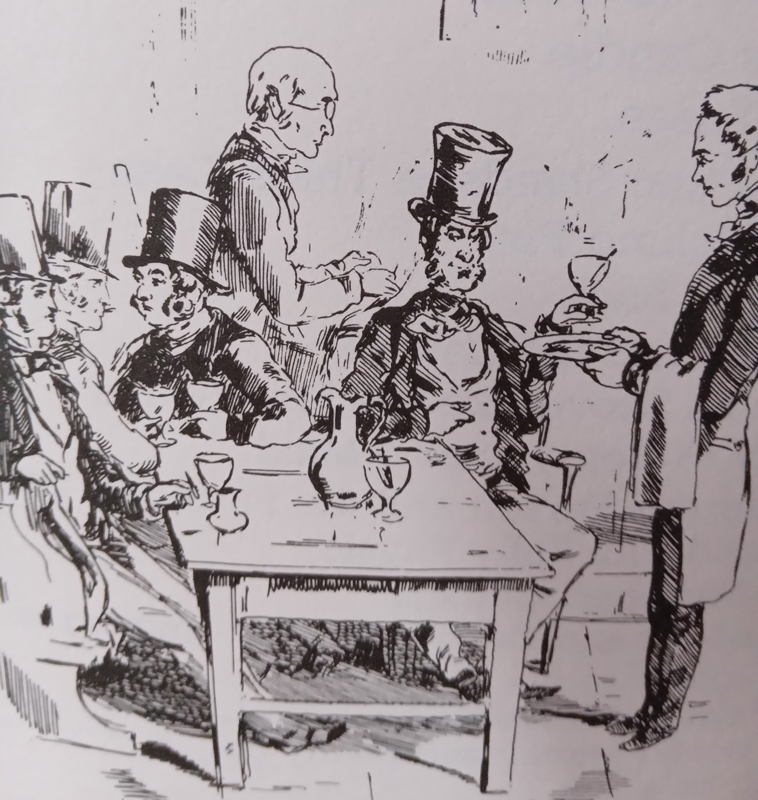

And there had, of course, always been a tradition of tavern singsongs. But by the 1830s, a number of establishments in London had gained in popularity for providing food and drink, accompanied by regular singing.

The songs were, in the beginning, sung by the landlord or the patrons of the house. But gradually, semi-professional and then fully professional singers were introduced to build up the program.

The clientele of these establishments were exclusively male, young bucks out for a good time, hack writers and soldiers. Some of these places assumed a kind of mock respectability, but behind the heavy hints and veiled allusions lay a bedrock of obscenity that pushed the boundaries of decency to its very limits.

Very much like the jazz and blues clubs of the 1950s and 60s, these premises were packed with clients literally shoulder-to-shoulder, like sardines in a tin, the smell of beer, tobacco smoke and sweat hanging heavy in the fetid atmosphere.

They had names such as The Coal Hole, The Cave of Harmony, The Back Kitchen and The Cider Cellars, which gives some idea of what they must have been like.

The English writer William Makepeace Thackeray recorded that The Back Kitchen was “a singing house frequented by young blades, apprentices, rakish medical students, handsome young guardsmen, young bucks, and even members of the aristocracy.”

From this description, it would seem that he had first-hand knowledge of this establishment. No doubt obtained purely in the interests of research, of course.

Dishes such as sausages and mash, poached eggs and kidneys, or deviled turkey might be served in these places. Drinks on offer would include stout, punch, brandy, whiskey, sherry and water, gin twist and a beverage known as champagne cup.

But what were these songs that were so unsuitable for the ears of respectable society, rendered with such great enthusiasm in the sweaty gloom of the Coal Hole and The Cave of Harmony?

Bawdy songs have a long and not entirely dishonorable place in the English tradition. Shakespeare, that lusty lad of 16th century Warwickshire, would have known them well, and when Ophelia lost her wits, her mind turned to a vulgar popular ditty that the Bard must have learnt in the country lanes around Stratford-upon-Avon:

… Alack, and fie for shame/Young men will do’t, if they come to’t/By cock they are to blame…

And when the folklorist Cecil Sharp was collecting rural ballads at the end of the 19th century, he recorded – but tellingly omitted to record in print – the suggestive words of Gently Johnny my Jingaloo, which contained lyrics that left little to the listener’s imagination.

Other songs went back as far as the early 18th century. One ballad contained the lines My pretty maid, I fain would know/What thing it is will breed delight/That thrives to stand, yet cannot go/That feeds the mouth that cannot bite…

Then there was the poetically explicit It is a shaft of Cupid’s cut/Twill serve to rove, to prick, to butt/There’s never a maid but, by her will/Will keep it in her quiver still…

By the middle of the 19th century, there was a thriving industry in bawdy songs with titles such as The Bower that Stands in Thigh Lane, The Friar’s Candle, The Amorous Parson and the Farmer’s Wife, There is No Shove like the First Shove and Sally’s Thatched Cottage.

These were published in booklets by a figure on the fringes of the pornographic book trade, one William West. He was a print seller who, in 1811, realized that there was a growing demand for songs of this nature.

Most of these ballads adopted existing melodies, and many parodied the original lyrics, using everyday objects as sexual metaphors, such as ‘drummer’s stick’, ‘rolling pin’ ‘friar’s candle’ and perhaps the rather more obscure ‘flea shooter’.

Nevertheless, like all forms of niche entertainment, the dens and clubs eventually gave way to the burgeoning music halls that were increasing in popularity across Britain as an expanding working class sought relief from the long hours and factory drudgery of the growing Victorian economy.

But once the form entered the relatively more refined domains of the theater, a clean-up operation was set in motion. Blatant metaphor turned into milder euphemism, pointed parody became the more gently humorous, and outright obscenity soon became confined and relegated to a handful of drinking dens that were frequented only by the lowest of the low, the detritus of humanity.

It seems, however, that despite the passage of time and changing tastes, human nature never changes, resolutely maintaining intact all its prejudices, hypocrisies, and repressiveness.

For today’s Britain is a dichotomy. On the one hand, there is the everyday, ever-present sexualization of national life. But on the other hand, there is a revived, post-1960s puritanical instinct that perhaps has more in common with aspects of 17th century England, the same impulse that would cross the Atlantic and was such a driving spiritual force among the early settlers of the American continent.

Yet behind the respectable, mainstream façade of every age, there lies the eternal, naked underbelly of crudity – vulgarities, either in verse, prose, or song – that never seem to lose their appeal, and for which there will always be an audience… ready and willing to listen, enjoy and participate.

Brilliant research, John, and elegantly written. A delight to read.

Thanks for that, Paul – it’s much appreciated.

Very informative article. In reference to the late television programme “The Good Old Days” there was also its predecessor BBC Radio’s “Palace of Variety” with Rob Curry as Chairman. I used to listen to “Palace of Varieties” as a boy – as did the rest of my family. A member of my family had an early tape recorder and recorded some of the broadcasts. A good job, too, as many of the original broadcasts were, possibly, “wiped” by the Beeb.