A flurry of notes from the lead guitar, then a blast of forceful brass kicks off the album with a wonderfully arranged intro. The plucking rhythm guitar picks up a two-bar repeating refrain which carries on for almost nine minutes. The shifting, halting rhythms of drums, bass and percussion lock together like a puzzle, breaking into interludes in perfect stride, along with generous solos in turn from the roaring tenor sax, the strident lead guitar and the joyous and tantalizingly discordant organ. The backup singers sound as relaxed and familiar as your uncles at a barbecue. And above it all, a transcendent voice is soaring. Soaring to the heights; soaring above the expressible.

The voice is Salif Keita’s. It raises the hairs on my neck, permeates my being and stirs me to my heart. I’ve never heard music like this. This is Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux with Salif Keita: Tounkan/Mana Mani, recorded in early 1981 in Washington D.C. The kings of seventies Western African music recorded at their peak in the studio they deserve. This is the one album I could listen to on repeat until the end of time.

It’s still not available for streaming in the US. Released in France, I found it online while abroad in Scandinavia and downloaded the mp3s, bringing them home with me to America. This is my stolen treasure. How can it be so good? Who are these ambassadors of West Africa, each a musical giant in their own right, plucked from different countries to form one supergroup?

They were so good, so gifted and unassailably dominant that they won the collaboration of the greatest singer of his generation; the young Malian Salif Keita, the noble-born albino who could sing like an angel of Allah, who would later relocate to Paris and become an international world music sensation, releasing fusion albums with heavy electronic production, in midlife returning to the acoustic instrumentation of his home region. Some great albums, some good ones. It doesn’t matter. The purity of his voice overcomes all obstacles and bridges cultures, religions, decades, languages and continents.

My older brother Miles and I have shared our love of music since youth, and one day while on leave from university he gave me my introduction to Salif Keita. At the time, Miles was a bass player and music major whose senior concert was a rollicking show of original Afrobeat songs with a ten-piece band.

He played Yamore, the opening song on Keita’s seminal album Moffou, recorded in 2002 in Bamako, a return to Keita’s roots personally and musically after his long Parisian sojourn. Now sitting together in our childhood home outside Boston, Miles laid it on me. The voice hit me like a force of nature. The rawness, the realness, with no filter; nothing between my ears and the soul of a man. No pretense, no pride, nothing more or less than a man singing as if he was facing his God.

After that I couldn’t stop listening, and I collected every recording could find; everything on iTunes and my secret music source, ripped CDs from the public library. I was in a period of transition in my life, and I needed it. Something in his voice spoke to me so deeply, inspired me, and pushed me forward into a life that was my own.

His music stayed with me as time passed. Then on a trip to Europe, I found Tounkan/Mana Mani and discovered my musical hero in an earlier iteration of nascent mastery; still a provincial young man of Africa, not a solo artist or world music superstar but un ambassadeur.

As a sax player myself I find it hard to listen to many of the horn parts in early African studio recordings. In the sixties and seventies into the eighties, the fidelity was lacking, resulting in crackling, tinny recordings, as if heard through a hundred yard pipe. Somehow the brass suffered the most, with great trumpeters, saxophonists and trombonists reduced to kazoo players. Only the greatest and most commercially successful, such as Fela Kuti of Nigeria, commanded the financial resources to ensure a world quality studio recording.

Part of a double album, the other half of the self-titled Les Ambassadeurs Internationeaux with Salif Keita: Mandjou/Seydou Bathily, unfortunately suffers the fate of so many other contemporary African recordings. But Tounkan/Mana Mani, recorded overseas, is perfect. A gem. So clear and precisely recorded for posterity, it’s a perfectly faceted musical piece at once complex and simple, capturing the spirit of a modernizing West Africa and their Golden Voice, the Mansa of Mali, Salif Keita.

When Sina Keita was a young man in Dakar, a marabout, an Islamic holy man, told him that he would have a son that would be outstanding in every way. Years later, his son Salif was born, in 1949 in the village of Djoliba, Mali, in a world bridged between the tradition of animism, the indigenous religion of Africa, and the reforms of Islam. On the tension of this bridging, young Salif’s very life hung in the balance. He was born an albino in a society which for many generations had considered albinism a curse. To this day, all across the continent, albino children are murdered in brutal animistic rituals.

Initially Sina was upset that his son had been born white and cast his wife and the boy out of the house, however the local imam convinced him to accept his son and the will of God. As Salif grew up he and his father developed an unshakeable mutual love and respect. Salif said of Sina, “He raised a large family, and in my lifetime, I never saw him do harm to anyone, and this influenced me very much.”

As for Salif’s own religious beliefs, he always knew where he stood. “I believe I was born with a faith in God. I’ve never agreed with animism from the day I was born, although I was born into it,” Salif stated in the 1991 documentary, Destiny of a Noble Outcast. As a boy Salif loved Qur’an school and he was deeply affected by the singing of the Qur’an school teacher. To his disappointment his father sent him to the French school, however he always maintained a deep devotion to Islam. He would later say, “I haven’t studied the Qur’an but I’m fighting for God’s cause. For the love of God.”

It was at school where he experienced the ostracism that would plague his young life, based in deeply held prejudice towards albinos. “From the age of five, when I understood I wasn’t the same color as the others I began to worry about my fate. When an albino passed by, people used to spit on the ground. And that hurt, that hurt. The first day my father took me to school, I didn’t want to go. When the other pupils saw me they were scared of me. I was afraid of mixing with them. It was then that my cursed fate began.” Salif spent his young life bullied, isolated from his peers and under implicit mortal threat, all for a condition he inherited at birth and for which he was helpless.

Aside from his albinism, the defining characteristic of Salif’s birth was his noble blood. The Keita family are direct descendants of the great thirteenth century emperor Sundiata Keita, founder of the Mali Empire. They are known as Gniame, the purest and highest of the Mande aristocracy. Though a nobleman, Sina made his vocation as a farmer, however he maintained the pride of his ancestry and of the ancient social structure. As Salif concisely stated, “Power is no longer in the hands of the aristocracy but that doesn’t stop us from being noblemen.”

One of the traditions of Mande social structure is a strict taboo against noblemen singing or playing music. This role was to be filled by the griots, a class of traditional singers and musicians who specialize in the Malian classical harp, called the kora. As a nobleman, Sina was serenaded by a griot named Kaba, who deeply influenced young Salif. “I liked the sound of the music, because for me, from the very beginning, music had power and was magical. Later, when I understood it better, it was also spiritual for me: it was the only way that I could touch God.” Yet Salif was discouraged from learning music himself, and this social restriction would prove significant for Salif when he came of age.

During summers out of school, Salif would spend his days in his father’s fields, vocalizing at the top of his lungs to scare hungry monkeys from the crops, and he says this is where he learned to sing. He picked up the guitar, and over time the music grew in him with an unstoppable force. Against the strong opposition of his family, he decided to become a musician and at the age of eighteen he moved to the Malian capital of Bamako. He slept in an outdoor market and would play for the patrons of local bars, who would tip him generously for his performances.

“The world evolves,” he would later say. “The process of evolution is assured by the betrayal of one generation by the next. Tradition says that noblemen shouldn’t play music, but deep in my conscience there isn’t a problem… I have a great respect for my parents past but I don’t want it to influence the present. Now it’s better to try another way of being noble.” He felt that, just as his father had his farm, he had the right to choose his own profession. And given the ostracism he faced an as albino, he didn’t have many choices.

On the strength of his solo performances, Salif’s reputation in Bamako grew and in 1970 he joined his first band, The Rail Band, which held a residency at the hotel bar of Bamako’s only rail station and was sponsored by railway administration. They combined the traditional music of Mali with electrical instrumentation and Afro-Latin jazz influence. Already widely admired, the band’s renown slowly grew into regional and eventually worldwide fame.

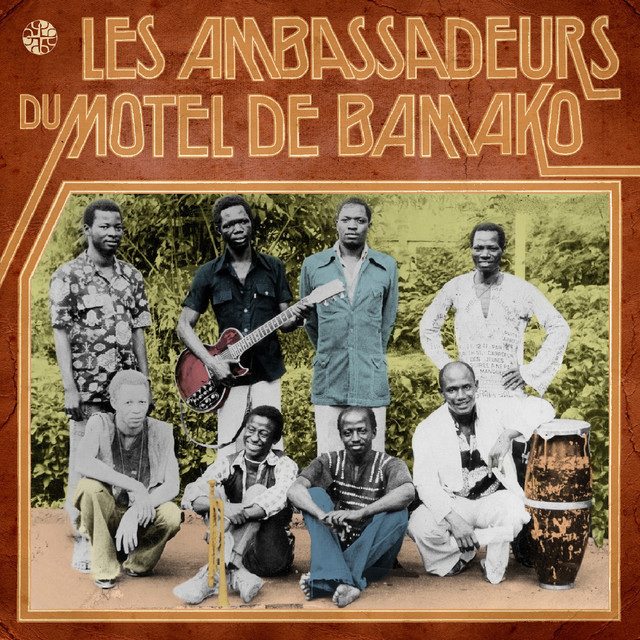

That same year a high-ranking official in Mali’s military government, Lt. Tiékoro Bagayoko, who had made his name as the arresting officer of Mali’s former president during the 1968 military coup d’etat, set out to create his own band to vie with the Rail Band for supremacy on the Bamako circuit. He partnered with the well-heeled Motel de Bamako and assembled a house band of prominent musicians from Mali, Nigeria, Guinea, Senegal and the Ivory Coast. The multi-national band became known as Les Ambassadeurs du Motel de Bamako, and every week from Wednesday to Saturday night they entertained the rich and powerful of the city. They rose in prominence socially and musically, winning a musical coup of their own when they poached Salif Keita from the rival Rail Band in 1973. They proceeded to build on the innovations of the Bamako music scene, blending regional and international influences into a new Malian pop which itself became the gold standard.

There are two grainy black and white videos on YouTube of Les Ambassadeurs in the seventies performing in matching tailored shirts on a TV soundstage. Salif, a white-skinned man amongst black men, closes his eyes when singing as if lost in an inner world. Salif and two other singers perform coordinated dances and though he executes them deftly, he seems so young and slight, like a graceful egret walking on land. His place is not on the ground, his place is soaring in the heights of human feeling.

The percussionist smiles and jumps. The lead guitarist Kante Manfila, a legend in his own right, wears a lighter cloth which identifies him as the band leader. His guitar lines command and proclaim. He and Keita shared the duties of songwriting.

After years of residency at the motel, their patron Tiékoro Bagayoko abruptly fell out of favor with the military junta and in 1978 was sent into forced labor where he soon met his death. The band’s association with Bagayoko left them in danger and they were forced to flee to Abidjan, Ivory Coast, narrowly escaping arrest at the border. Now based in Abidjan, they renamed themselves Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux.

Released from the insular environment of the residency at Motel de Bamako, the group set their sights outwards, touring the region and releasing a hit single, Mandjou, a renewal of a traditional griot praise song, written by Keita in honor of the Guinean president Sekou Toure. The politician had long been a supporter of the band and of Keita in particular, awarding him the Guinean Order of Merit in 1976.

Soon the band received a grant from the Rockefeller Foundation to travel to the United States and record with the Congolese producer and keyboardist Ray Lema. They were hosted at the Guinean embassy in Washington D.C. at the invitation of Sekou Toure, and it was during their stay in the American capital in early 1981 that they set into record Tounkan/Mana Mani.

The album crystallizes a point in Keita’s career. At thirty-one years old with over a decade in music under his belt since first arriving in Bamako, he was firmly established regionally as a popular singer and songwriter. Les Ambassadeurs had been forged in the fire of years of nightly shows at the motel. On Tounkan/Mana Mani, they play seven and eight, and up to ten and twelve minute songs, with vamping rhythms. They are in no hurry, rather they’re content to simply enjoy the timeless and joyful energy of the music. Salif is experienced and confident, already I’m sure with dreams of reaching the world stage. It’s a perfect encapsulation of a moment in time for Keita, a fledgling bird enjoying mastery of his environment.

In another excerpt of concert footage with the band, this time captured in 1984, Salif is out front, clearly the leader and more confident in his carriage, performing a long play-act with the guitarist. His star is growing beyond Africa, soon to shine the world over.

Les Ambassadeurs had travelled to Paris in 1974, performing for homesick Malian factory workers. In 1984, Salif returned to Paris to stay, relocating to the Parisian suburb of Montreuil, the center of Malian settlement in the city. As he found his way in a new continent he performed at events and concerts for the Malian immigrant community.

Possessing a wide-ranging musical taste, Salif was a fan of Western pop music. He made the decision to bring African and Western styles together and incorporate electronic instruments and production techniques. As he stated in 1991, “Just as one era in life is determined by one generation, so a kind of music, a kind of culture is determined by the rhythm and the melody… so if you only play the rhythm and the melody and don’t mix anything modern in it, if you don’t want to open up to a more universal music, you might as well keep that music in a museum. It’s OK, but put it in a museum for the tourists. But the moment you want to explode before the eyes of the world, the moment you want to be heard and to be ideologically useful for society, then you have to know how to speak to people. It’s a step towards social harmony, a step against racism. A step towards peace. Because the more we mix together the less social problems there will be, because there will be an exchange of cultures.”

A remarkably intelligent and self-aware poet-philosopher, he accomplished his musical goals with the release of his 1987 breakout fusion album Soro. In 1988 he was invited to perform at Wembley stadium in London with a range international superstars in honor of the 70th birthday of the greatly revered, yet still imprisoned, political leader of South Africa, Nelson Mandela. In 1991 Salif released his greatest fusion album, Amen, to worldwide acclaim. Keita would go on win many international awards including multiple Grammies.

A decade later with the release of Moffou he had once again evolved. He said in 2006, “I think I found the road that I must follow. I must try to combine my experience and my sensibility. Me, I always wanted to do acoustic music with a lot of heart, a lot of soul, without a lot of electronics. This is what I have been wanting to research. I think I’ve found my road.”

I love the disparate eras of Keita’s musical journey; each holds its own power and beauty. But somehow I always find myself returning to Tounkan/Mana Mani. There is a pureness of joy and contentment in the music that I never tire of. It’s a throwback to a former world, when the ancient village life of Mali was first facing the swelling tide of Western culture, commerce and media that came with the great cultural changes of the 1960s. There is a sense in Tounkan/Mana Mani of being at home, amongst loved ones, enjoying the timeless rhythm, the wonderful timbre of the instruments, and the voice that calls us home to our own heart.

Amidst the onslaught of Western cultural influence which evoked both fascination and disorientation, Les Ambassadeurs created a modern music that West Africans could call their own. “Above all,” Keita said, “They taught Malians to love their own music.”

In 2005 he founded the Salif Keita Global Foundation to assist persons with albinism at a global level. “Albinos have problems integrating into society,” he said, “which is something we wanted to expose. We are saying that beauty lies in difference. We must be proud of what we are.” He continues to raise awareness both through his foundation and through his music, releasing two albums themed around albinism, 2010’s La Difference (The Difference) and 2018’s Un Autre Blanc (Another White). The music he has made and continues to make throughout his long career holds great personal significance for me and for so many around the world.

Music creates peace. Music saves lives. Music shows us who we truly are; it seeps into the soul and changes how we see ourselves and our place in the world. Many possess great talent and can play wonderfully, with technical prowess that can make your jaw drop. But do you have something real to share? Show me what life means to you, the bare heart and the authenticity with which you approach every day and every person you meet. Are you willing to give everything you have, is it worth it to you?

This is why we love our musical heroes; Freddie Mercury, Bob Dylan, Prince, Mozart, John Coltrane, Kurt Cobain, Hank Williams, Muddy Waters, Elvis Presley, 2Pac, Bob Marley, Louis Armstrong and countless others. This is why their legacies outlast their own contemporary period and their own lives and are carried on in future generations. And standing shoulder to shoulder with the greatest vocalists and composers of the first century of recorded music is Salif Keita.

Mr. Keita himself put it eloquently, “I believe that all musicians, all artists are prophets in a way. Because art comes from the heart and to do it well you have to be very sensitive. And a sensitive heart is a noble one. A prophet’s heart.”

Sources:

Les Ambassadeurs Internationaux with Salif Keita: Tounkan/Mana Mani (1981):

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=PLTme-Fk0s2At6uMBCY04bUakiJJAtbugv

Destiny of a Noble Outcast (1991):

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YddCALG4qJE&ab_channel=OFFICIALSALIFKEITACHANNEL

Footage:

Les Ambassadeurs 1970s:

https://youtu.be/WgUbtVhnTRI

https://youtu.be/T-4nyr5GbwQ

Les Ambassadeurs 1984:

Salif Keita Wembley Stadium 1988

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=V5RCgmYJJdg&ab_channel=MamadouSEKK-LeBergerDesArts

Articles:

http://www.andymorganwrites.com/les-ambassadeurs-malis-musical-revolutionaries/

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Salif-Keita-Malian-singer-songwriter

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Salif_Keita

https://afrostylemag.com/ASM7/issue5/salif-keita.php.html

https://www.theafricareport.com/94831/salif-keita-mandjou-a-griots-praise-song-for-a-president/

https://www.wrasserecords.com/Salif_Keita_7/biography.htmlhttps://www.nytimes.com/1995/01/29/magazine/beat-king-salif-keita.html