They call themselves Tinariwen, which is the Tamashek plural for desert or open space. An open space is how they insisted the Minneapolis-based Cedar arrange themselves for their show on November 16th. All the chairs have been stacked and put away save for a few short rows on either end of the large dance floor in front of the stage. The band wanted an audience that could move about and respond fluidly to their trance-like music.

People-watching is particularly interesting this evening. With over 300 tickets sold before the show opened, the hall, one of the smallest venues Tinariwen has ever used, is very full. Many more tickets are sold at the door. Most attendees, it seems, are not familiar with the idea of free-style movement. At least, they don’t participate beyond a sheep-like nodding of their heads and sporadic bouncing on their heels. But there are a few inspired souls who writhe like snakes in the throes of death.

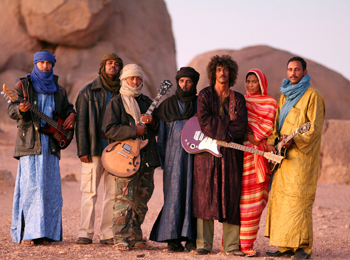

Tinariwen identify themselves as “the ambassadors of one of the oldest and proudest people on earth”—the Tuareg. These nomadic peoples had formerly populated much of the northern Saharan desert, but found their land artificially divided when, following the independence of African countries in 1960, the modern nations of Niger, Mali, Algeria, Libya, and Burkina Faso were created.

The music this night suggests the landscape that is their home: constant, mesmerizing, and spare of ornamentation. One song blends into the next with an occasional ripple in the river of music that comes in the form of volume variation or solo riff of a guitar. Sometimes one of the guitarists leads the audience in an arrhythmic clapping that yet resembles a pattern. The end of the songs comes abruptly like the turning off of a faucet.

About thirty minutes into their single set, one guitarist begins chanting a song reminiscent of French rap, which proves to be very popular with the crowd. Up until now, the songs have been sung in the indigenous language of the Tuareg—Tamashek.

Tinariwen says that they play their music to teach others about the beauty of their desert home and the strength and dignity of the nomad and his way of life. Although most of us cannot understand the words, we see their beautiful clothing, embroidered with rich, colorful threads and eye their handsome headwear with curiosity and admiration.

Forty-five minutes into the show, the band plays their most irresistible number, yet. Many in the audience begin mimicking the initial serpentine dancers as the drummer and bass player help the dancers along. Immediately following this piece, they perform a song flavored with the influences of Carlos Santana with whom they performed at the Montreux Jazz Festival in 2006.

Tinariwen also sings about the problems of poverty, oppression and lack of development which continue to hamper their progress in the desert. In fact, at their website they list the political evolution of their lands since the late 1800s. Their music is driven, like sand, speaking of the plight of their people.

The mostly-white crowd listening to this band from the Saharan desert, while physically reserved, shows their enthusiasm by applauding loudly after each song. Surprisingly, after barely an hour of performance, the band retires to the green room. Startled, the audience thunders their applause until the band returns for two more short encores.

Author: slb2

Susan Budig draws from music and poetry to create her own poems that she uses to bring healing and recovering from grief to others.