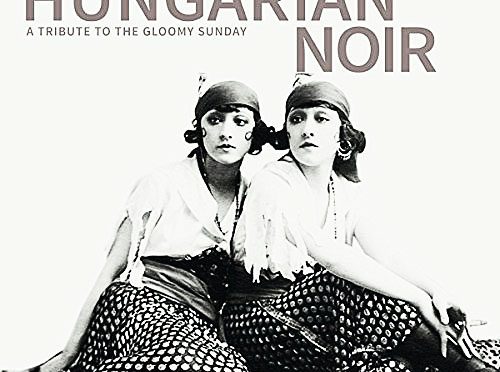

Various Artists – Hungarian Noir – A Tribute to the Gloomy Sunday (Piranha, 2016)

Odd submissions are just part and parcel to music reviewer, but I’ve never received a submission with a health warning. Well, until I received a copy of Piranha’s Hungarian Noir A Tribute to the Gloomy Sunday, set for release on May 13th. According to the cover warning “This music may be hazardous to your health. Listening precaution is advised.” Really? Sounds like a dare, doesn’t it.

I’ll admit that some music does provoke strong emotions, but that’s usually some homicidal tendencies as a result of some irritating bit of pop music that’s played over and over. That I might fall victim to a piece of music is another whole ball of wax. A threat to one’s personal health doesn’t seem like a likely profitable way to promote a music recording, but hey, I’m game. Okay, so I have listened to all 12 tracks, differing versions of the same song on Hungarian Noir a couple of times now and I’ve haven’t lapsed into a coma, developed a suspicious rash or run amok about the neighborhood. Do I possess a natural resistance to the dark lure of “Gloomy Sunday?” Or is this all a bunch of hooey?

A little background is in order. Regarded as the “Hungarian Suicide Song,” “Gloomy Sunday was published in 1933, a work by the pianist and composer Rezso Seress. Mr. Seress’s original lyrics went along the lines “The world is ending,” expressing the despair of war and the sins of humanity. It was poet Laszlo Javor who entitled his version “Szomoru vasamap” or “Sad Sunday,” re-wrote the lyrics that would stick in popular song over the original lyrics by Mr. Seress, with the song recounting the singer’s suicidal thoughts over a lover’s death.

The first recorded version of the song appeared in 1935 by Hungarian Pal Kalmar. A year later “Gloomy Sunday” was recording with English lyrics by Sam M. Lewis and performed by Hal Kemp. Another version also appeared in 1936 with the lyrics this time by Desmond Carter and performed by Paul Robeson. Perhaps the most famous recording of “Gloomy Sunday” is the 1941 version by Billie Holiday.

Okay, here’s where things get freaky. According to rumor and several 1930s press reports, the song has been associated with some 19 suicides in Hungary and the United States. And, here’s where things get a little sketchy. According to the press release I received, an American newspaper (no accredited publication was named) reported, “Budapest police have branded the song ‘Gloomy Sunday’ public menace No. 1 and have asked all musicians and orchestras to cooperate in suppressing it, dispatches said today.”

Apparently as the unnamed publication reports, “Men, women and children are among the victims. Two people shot themselves while gypsies played the melancholy notes on violins. Some killed themselves while listening to it on gramophone records in their homes. Two housemaids cut their employers’ linens and paintings and then killed themselves after hearing the song drifting up into the servant’s hall from dinner parties.”

If that weren’t enough, the BBC (British Broadcasting Corporation) banned broadcast of the Billie Holiday version during World War II, citing it being bad for morale – a ban that wouldn’t be lifted until 2002. Now, here’s the kicker, composer of “Gloomy Sunday,” sad Mr. Seress killed himself in January of 1968.

World War I ended in 1918 and left some 17 million people dead and another 20 million wounded as well as a well-worn path of destruction, disease and famine. The 1930s saw the creeping advances of the global economic havoc of the Great Depression and news reports are chalking up suicide deaths to a song? Seriously? And, don’t get me started on the racist overtones of the idiotic reports about suicides “while gypsies played the melancholy notes on violins.” While all the reports might just be just chalked up to anecdotal urban legend, people at the time took the warning seriously. Good thing for music lovers, musicians are more than willing to tempt fate and take on a creepy urban legend. Nothing dispels public panic better than a good artistic poke in the eye.

I’ll admit “Gloomy Sunday” the song itself is fairly morose. Good thing Piranha offers up some goodies on Hungarian Noir like the opening version by the Cuban group Vocal Sampling or “Domingo Sombrio” by Mozambican Wazimbo featuring Kakana or lushly cool and brassy “Trieste Domingo” by Cuban Manolito Simonet y Su Trabuco. There’s enough of a change of pace, but there is no denying it is the same song over and over, despite the rap version “Travessia” by GOG featuring Pianola, or the breezily jazzy “Gloomy Sunday” by Glenda Lopez or “Triste Domingo” offered up by Argentine musician Chango Spasiuk.

Fans also get a dose “Gloomy Sunday” by way of Colombia’s Bambarabanda on “Triste Domingo” and Hungary’s Cimbalom Duo on “Szormoru Vasarnap.” As a bonus, fans get the sweetly melancholic vocals of Billie Holiday and her version of “Gloomy Sunday” before the recording ends with Pal Kalmar’s moody version replete with tolling bells and sad strings.

I don’t think listeners are taking their own lives in their hands with Hungarian Noir considering I have no intelligence to support that the U.S. military is using “Gloomy Sunday” to currently fight Islamic State, the Taliban or Kim Jong Un. While I’m all in favor of giving superstitious gobbledygook a good poke in the nose, this is one of those recordings where you really have to want to listen to varying versions of the same song.

Author: TJ Nelson

TJ Nelson is a regular CD reviewer and editor at World Music Central. She is also a fiction writer. Check out her latest book, Chasing Athena’s Shadow.

Set in Pineboro, North Carolina, Chasing Athena’s Shadow follows the adventures of Grace, an adult literacy teacher, as she seeks to solve a long forgotten family mystery. Her charmingly dysfunctional family is of little help in her quest. Along with her best friends, an attractive Mexican teacher and an amiable gay chef, Grace must find the one fading memory that holds the key to why Grace’s great-grandmother, Athena, shot her husband on the courthouse steps in 1931.

Traversing the line between the Old South and New South, Grace will have to dig into the past to uncover Athena’s true crime.